Lynx — the long awaited 2-pin tele binding from 22 Designs has arrived. And how!

Whether you earn your tele turns or not, Lynx has a lot to like. The inherent functionality remains the same as the beta binding — 2-pin toes deliver better edging and unsurpassed touring. An NTN mid-sole connection makes smooth tele turns with instant engagement. Hard to not like that, even if you’re a duckbilled tele zealot. Nearly all the short comings of the beta version are addressed and cleaned up in the production version.

- New Compression Springs

- Case-hardened steel pins

- Stronger 7075 aluminum jaws

- Stronger, flexible toe bumper

- Deeper notches in claw mode-switch cam

- Simpler spring pre-load adjustment

Stepping In

Lynx is about as easy to step into as a 2-pin fiddler binding can be. Two towers of black plastic in front of the toe arms help you position the tip of your boot so you can just press down and close the pins securely on the boot. They don’t close with the same resounding snap as an Ion or Vipec, but a close second. It’s about on par with Meidjo. If you’re touring, the claw should already be recessed; just step lightly on it with your boot so it latches down flat before clicking in at the pins. Then, lock out the toe by lifting the toe lever until it blocks the jaws one or two clicks.

To transition from skinning, with your heel raised a bit, lift up the claw with the beak of your ski pole grip so it stays upright, then step down so it latches onto the 2nd heel. It won’t give much of an audible or tactile clue that it has hooked on, so lift your heel and you’ll feel the resistance of Lynx’ power train to confirm you’re loaded for tele turns.

Stepping Out

To exit the binding push the toe lever down to open the toe pins. Once open, lift and twist ’til your boot swings free of the claw. Super easy once you break the habit of disconnecting at the heel first. Naysayers have complained that you can’t disengage the claw without disconnecting at the toe. That’s true; so if you prefer a totally free pivot for crossing a flat after a pitch of turns you’ll have to make a short pit stop to disconnect the duckbutt. Let me offer three thoughts on that. First, ordinarily if you’re switching to a free-pivot it’s to skin up so you’re taking skis off anyway to add skins. In another case, such as when crossing a short flat zone, a meadow or traverse, you should revel in the fact that, unlike your AT buddies, your heel is already free enough to shuffle a short stretch without whining. And in the case where it’s a longer section begging for a free-pivot, disengaging to push the claw down and then reconnecting really doesn’t take that much time. Again, far less than the shift logistics your AT buddies must do in the same situation (except for Vipec users).

Turns

…you can count on Lynx to help you hold an edge when you can’t afford to lose it.

What nearly everybody is going to love â L.U.V. â is the engagement and tele sensation of Lynx. It is solid like the Outlaw, not quite as firm as Axl, but the tele-resistance engages immediately — certainly faster than Axl, arguably faster than Outlaw. On the hill, making turns, I couldn’t tell the difference between the cat and the villain. On the carpet you can feel Outlaw has a bit more play in the heel than Lynx for the first degree of heel lift, but the difference is academic since no one skis carpet. What is more noticeable is how quickly the flex resistance turns on thanks to the use of composite plates that act like leaf springs at the first hint of raising heel. It adds a confidence that belies Lynx diminutive size and weight. That sort of engagement is typically reserved for heavier bindings, like Outlaw, Axl, or grandpa Hammerhead.

The other part of the downhill equation is the toe connection. Experience proves 2-pins transfer more lateral power to ski edges than a toe cage. In some cases you really can’t tell, like between Outlaw and Lynx. However, between a 75mm wedgie toe and a low-tech toe connection, the improvement is undeniable to any who have tried both. On hardpack you can count on Lynx to help you hold an edge when you can’t afford to lose it. And yet, in champagne powder the NTN connection moderates the tip pressure so you don’t submarine in the deep — unless, of course, you want to. 😉

Touring Efficiency

You already know 2-pin toes are the definition of state-of-the-art touring efficiency. That’s the advantage Lynx delivers over Outlaw â provided that matters to you. From the standpoint of durability, 22 Designs is using strong 7075 aluminum for the jaws, and case-hardened steel pins with ice cutting grooves cut in them to help removed snow packed into the boot inserts. You might still need to manually clean out your inserts if the snow is hardened into ice. The toe lock out worked fine in the beta version so, absent any evidence to the contrary, I’m trusting it still is.

In the same spirit of trust the tendency for Lynx to ice up is minimal. I did notice snow building up on the composite plates to a thickness corresponding to the height of the retracted claw — not much and only in humid conditions. It may have created a snow wedge under my boot corresponding to a 2-degree climbing post. Noticeable, hardly debilitating, and rare. It might even reduce your tendency to engage any of the climbing wires, especially if you’re a low-angle meanderthal like yours truly.

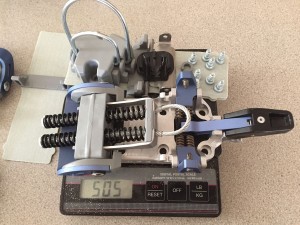

Prior to the advent of free-pivot tele bindings weight was the baseline for determining efficiency. With the right components you could build a DIY TTS binding that is lighter, but to save those few grams you’ll be sacrificing the NTN connection and downhill performance. At roughly a pound per foot (505 g / 17¾ oz.), Lynx qualifies as one of the lightest NTN bindings available.

Releasability

The usual caveat: Lynx exhibits “tele release” capability. It is possible, not reliable. 22 Designs does not guarantee release.

I was able to kick my boot out of a binding on flat ground. To me, this confirms the possiblility of release. The side walls of the claw are lined with a plastic shim that has a nice radius to it. The spec of the second heel calls for the sidewalls to be beveled 10 degrees. With enough sideways force the claw can be pushed back allowing the boot to rotate out sideways. Not reliable, but possible.

It is also possible with Lynx for the toe jaws to open up. This is less likely than ejecting from the claw, except if there is ice stuck at the tip of the inserts causing the pins to be closer to the width where they can toggle open, causing a premature release.

22D says that a good way to know if there’s ice preventing the pins being fully seated is to make sure you can lock out the toe jaws at least two clicks. If you can’t do that, there’s probably ice in the inserts that needs to be cleaned out.

Tip: Use the tooth of a voile strap to clean out the insert.

Climbing Wires

One thing everybody in the tele community can celebrate, whether you’re using a 75mm or NTN boot, is the heel post. The ease of flipping up a spring-loaded climbing wire first seen in 22D’s Hammerheel is doubled with the Lynx climbing post. Two wires â a short and tall â are contained in this heel assembly. The short wire yields a 7° lift, the tall around 12° (less for big boots, more for small). The best part is this heel unit comes assembled — it doesn’t require you to push the plastic key holding the wires in place while simultaneously screwing it to the ski. Without regular practice this can be a moment of frustration that is thankfully now an historical footnote. Say Hallelujah! Say it again. Hallelujah! Hallelujah! Hallelujah!

One more benefit. It is just shy of an inch tall (23mm or 15/16″). That means it could work with many other telemark bindings that do not have spring activation of their climbing wire. You might need to shim this heel post to prevent a negative ramp angle, but that’s kindergarten DIY stuff.

Durability

22D has built a good reputation for making bindings that, if not indestructible — there’s always an outlier who can break anything — is what we might call âtele-hardened.â It’s made to withstand the repetitive pounding telemarkers impart to their gear. Lynx maintains that tradition by relying on metal and the strategic use of plastic. Many failures with telemark bindings occur as the result of excess pressures created from parts icing up and Lynx has minimal snow buildup.

Conclusion

The only reason not to consider adding Lynx to your list of gear to buy is you don’t have or intend to own an NTN boot with tech inserts. But if you do, or are, then the only reason to not get Lynx would be you’re already satisfied with Outlaw or Freeride and you insist on ski brakes. Lynx doesn’t have ’em, and probably never will. Optional crampons are available.

Still holding tight to your duckbills? Carry on. Don’t let me guilt you into switching platforms. Nonetheless I can’t help reminding you that even though 75mm gear rocks there is more performance available if you’re willing to make the switch. With Lynx your NTN rig would be undeniably lighter, more efficient skinning, provide more edge control, and a smooth(er), powerful tele sensation. If that don’t make ya purr, you’re an alpine skier.

22 Designs

Lynx

MSRP: $500

Weight (sm): 505 g ⋄ 17¾ oz.

Weight (lg): 525 g ⋄ 18½ oz.

Related Links

22D’s Lynx – Beta Report

First Look at 22D’s Lynx (Telemark Skier Feb. ’18)

22D’s Lynx – Low-tech powered by NTN (Telemark Skier Jan’18)

10 comments

Skip to comment form

Great review! I would rush out to get a pair of Lynx except, as an active Northeastern patroller (and, occasional, uphiller), I depend on the Outlaw and it’s brakes. Sure hope that “and probably never will” proves wrong!

Any feeling for where skis width may overwhelm the binding? Thinking of mounting on a a 106-108mm ski for good front side days and all backside days.

Tech pins actually increase edging power for tele turns so you should be find up to 110mm. What’s the limit? Ask your friends with Dynafiddle bindings how phat they would go.

Any thoughts on the downhill of Meidjo vs Lynx?

If you could ski blindfolded I doubt you could tell the difference. Some say Meidjo is more active. I’m numb to the difference.

Bit of a threadjack but I’m interested in your experience with the Outlaw brakes. I’m similarly situated but on aging Rottafella gear – Freeride / Freedom – and thinking about the Outlaw X the next time around but put off by a lot of negative comments on the brakes. I know the internet is primarily for negative feedback, so I assumed there were some silent satisfied skiers. But few (if any) have emerged from the silent majority/minority/whatever. What generation Outlaw – original or X? What brake width/ski width? Any tips or traps to be aware of on the path to dependability and satisfaction w/Outlaw brakes?

Without question go Outlaw X, have three Outlaw bindings. Broke all flex plates on the original prior to the redesign. Toe bails have now cracked on 1.5 pairs. 22 Designs have offered to replace to be fair but the X has none of those issues from what I can fathom. Any money saved on the older version will be spent re-mounting any failed bindings. As for the ski brakes, lot of people bitching about them being basic, etc. but having gotten used to them now they work really well once you get the technique down.

It takes a bit of time to get used to the brakes, well, really, it takes time to learn how to get your foot into the binding with the brakes. I had to practice on the carpet in front of the TV for several evenings… The Outlaw X has proved to be great, as a patroller there’s nothing more embarrassing than being the last off of scene because you can’t get your heel cable hooked up with out your ski sliding down ice patch; with practice, the Outlaw-X are as easy and reliable as my Fritschi’s on a steep slope. I am using the Outlaw-X’s ona pair of Fischer Mtn Pro’s (I think they are 98 mm wide underfoot). Just takes practice////

That’s exactly it – what I love about the Freeride is it’s almost as easy as an alpine binding. Even the Freeride can be tricky on steep hardpack, but the Outlaw sounds manageable too once I put in the time.

Thanks. No question it would be Outlaw X and glad to hear the brakes are workable.