The Year of the Thunderbolt

Muscat called me from the operating room late Tuesday night and said that because he was on call until six a.m. and had Wednesday off, and because, since it wasn’t a weekend, the nannie would be coming tomorrow to look after Rachel while his wife was at work, and because it was the best snow year since the nineteenth century, and because he was crazy, yes, he would climb and ski the Thunderbolt with me on a one-day lunatic ski excursion from New York City. As he told me this I imagined him wrestling an immense hypodermic into the jugular of yet another unconscious victim of Brooklyn gang-warfare, a procedure Muscat has told me is one of the most interesting in anesthesiology. So what if it was 175 miles each way, Paul continued, or that we had to be back by dinnertime or risk being terminated with extreme prejudice by our wives and psychologically scarring his two-year-old daughter, who would grow up thinking daddy loved Mr. Ramer more than her? So what if the weathermen were predicting an arctic February cold front to sweep through the region tomorrow? So what if we didn’t know where the trailhead was? We knew which mountain it was on. I packed my bags and hit the sack.Mt. Greylock, the highest peak in Massachusetts, sits just south of Williamstown, near where the Massachusetts, New York, and Vermont borders come together. At 3,491 feet, it doesn’t exactly scrape the sky, but after Mt. Washington, Katahdin, Mt. Mansfield and Camel’s Hump, Greylock offers some of the best backcountry skiing in New England, on trails cut specifically for the sport many decades ago. As all those other mountains are many hours further north, Greylock stands as the best and biggest backcountry prize in the region.

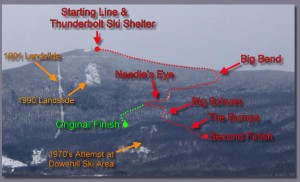

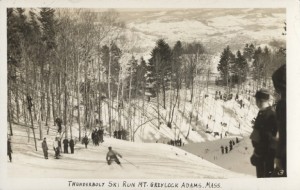

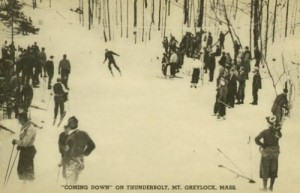

The king of Greylock ski trails is the Thunderbolt, a steep, twisting trail that drops down the eastern slope from summit to valley, a sustained pitch of 2,300 feet. Like many early ski trails, it was cut by the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) in the 1930s, and became the site of major competitions in the years before lifts. When that innovation came in, most of the original “A” racing trails cut in the east by the CCC, such as Mt. Mansfield’s Perry Merrill and Nose Dive, and New Hampshire’s Wildcat Trail and Cannon’s Taft Trail, were incorporated into lift-served ski areas. This didn’t happen to the Thunderbolt, which never saw anything other than a small, long-dismantled lift near the bottom, and a ski area off to its south side that went belly up years ago. Although it is starting to grow in, the trail remains a backcountry classic.

Greylock is small but looms large in America’s early consciousness of the mountains. Emerson counseled Thoreau when Thoreau revealed he was planning to climb it that it was a “serious mountain.” When Thoreau did go, in 1844, he wrote about sleeping at the summit under a door he’d found off its hinges in an abandoned shack, and the beauty of the view across the tops of the valley fog at dawn. Although we don’t know if he ever climbed it, Melville dedicated Pierre to the largest mountain he could see from his house just north of Pittsfield, comparing it to a king in purple robes. There’s even an eccentric theory that the mountain’s outline, clad in the clouds that give it its name, resembles…a great, white whale.Although I grew up in the Massachusetts Berkshires and skied almost every lift in the range as a boy, in the 1960s and 1970s, very few people went into the backcountry to ski. I had heard of the Thunderbolt, but never skied it. For one thing, in many of those years the snow that had once been so reliable developed the annoying habit of turning into rain before it reached the earth. So that February, when blizzard after blizzard buried southern New England and I found myself the proud possessor of a strong telemark turn cultivated in the Wasatch, I vowed it would be the Year of the Thunderbolt. All I needed to do was convince some other fool to make the trek with me. Enter Muscat.

Bleary-eyed from another desperate night of sewing people back together, Paul picked me up at seven on Monday, and, dressed almost as strangely as the hookers on 10th Avenue (albeit more warmly), we sped north on the Taconic Parkway. About three hours later, we were nosing around on unmarked roads at the base of the mountain, searching for the trailhead. After parking and then thrashing around in the woods, we finally found it, tucked into an unmarked drainage at the corner of a field that was once the finish area for races.The snow was copious. There were no tracks, and we took turns breaking trail, sinking in a foot on each step. It was deep, it was dry, it had no raincrust or wind damage, and it was one hell of a workout with only two people. As we wound our way up through the forest we began to realize that the weatherman had, for once, been right. Clouds were rippling the summit like prayer flags and when we stopped for lunch at a shelter about halfway up, we were cold in minutes. The fettuccine alfredo I had cooked for dinner the night before had congealed into frozen ganglia. It was pdisgusting to watch Paul eat his portion. Perhaps living so close to death on a daily basis has ruined his table manners. I have no such excuse.

Climbing New England trails is different from climbing above treeline, east or west, or even in the pine and aspen forests of the lower slopes of the Rockies. Again excepting Mt. Washington, Katahdin, and a few other isolated slide paths on the highest peaks, avalanche is never a problem, but views are rare and the terrain tends to buck and roll. Trails twist in every direction as they cross the folds of hollows and drainages. Successful touring in the east is less a question of picking a safe line to a ridge or summit, than of reading the maps carefully enough to make sure you’re on the right trail, as many of the best trails for skiing (or gaining access to the ski trails) are poorly marked, and rarely have lead tracks. Seclusion has its advantages. At one point we flushed a wild turkey from the brush. It lumbered off through the bare branches like a laden B-52.We decided not to skin the upper half of the trail, to save the snow and to avoid the steep grade, but ascended another ski trail with more switchbacks, the Bellows Pipe Trail. After seven switchbacks through deepening snow, we joined the Appalachian Trail, which runs across the top of both the Thunderbolt and Bellows Pipe as it descends northwards from the summit. Unsure of how far a walk it would be if we stayed on the deep snow of the AT, we decided to cross over the ridge a few hundred feet, then walk up the unplowed auto road. Big mistake. Although the snow had been compacted by snowmobilers, the road climbs very, very gradually, circling the summit cone almost twice before arriving. The light was beginning to fade, and the snowy hills below us and out to the Taconic Range to the west, the Berkshires to the south and east, and the Green Mountains to the north, began to dapple in the blues and oranges that come with sub-zero temperatures.

The obvious line on the left is a power line trail. The gash in the center, from a landslide. The Thunderbolt Trail winds around on the right side of this photo.

When the weather is that harsh, there has to be an implicit understanding of what needs to be done at every moment. Doctors are good at that. Hunkered down in the wind-shadow of the lodge, with hardly a word, we strapped on knee pads, adjusted laces and buckles, and coaxed frozen zippers. After scrabbling across the summit, we descended the Appalachian Trail to the north, and as soon as we dropped into the woods the snow improved and the wind calmed. By the time we’d descended the four hundred feet to the hard right-turn onto the Thunderbolt, we were gliding through squeeky cold snow over a foot deep, light and dry on a cushion thick enough to cover the chest-high brambles and saplings of summer. We made the turn onto the first steep pitch of the Thunderbolt proper, and the trail rolled away to the valley, a secret, unbroken stash of white in the late afternoon shadow, two thousand verts without a track in sight. The wind swirled in the treetops.

The first two pitches after the turn are the steepest, somewhere in the 35° range. After several hundred vertical feet it backs off, but still falls away nicely, a classic New England ski run. The designers knew their game and built in switchbacks, fall-away turns, open slopes with sudden views across the valley and multiple transitions in fall-line. To race it packed out and rutted must have been a long, fast, technical ride.

Accompanied by the ghosts of racers, we made hundreds of turns, the longest powder run I’ve ever had in New England. We forgot how cold we were and that the light was failing as we played through pitch after pitch of winter forest. When we approached the bottom, we traversed out to the abandoned ski area.Stumbling through the woods for a few minutes brought us out onto the gentle, open fields of the lower slopes. We coasted down to the car as darkness fell.Now all we had to do was thaw out, find some food, and get home. As we drove through downtown Adams, the thermometer on the bank read 12°. When we stopped in a diner to eat, we looked the way we felt, but they fed us anyway. Paul came up with the inspired idea of calling each other’s wives to say we would be several hours late, the theory being that when each woman first heard her husband’s friend’s voice, she would immediately worry that her own man had broken some vital part, and, on learning that he hadn’t, would be so relieved that she would forgive all minor transgressions.

It didn’t work.

About halfway through dinner, Paul looked up and said, “Davecantalkneemoh,” and began to slide down the orange vinyl like a junkie going into a nod. Starting to fade myself, I poured him into the car, which looked like we had recently robbed both a ski store and a fast food concession. Paul revived briefly around Poughkeepsie, insisting that when we stop for gas we buy gummy bears and apple juice in a convenience store whose fluorescent lights bit at our eyes. He still wore knee pads. Soon after that, we traversed the dark, snowless suburbs, then shot across the Harlem River onto the island of granite platforms, feeling as if we had left the natural world behind.

We’ve all felt it, the warp of reentering the hive after even a single day on some testing peak. And alpinists have been writing about the tension between going away and coming back for centuries. It’s been there from the beginning, maybe April 26, 1336, when the Italian humanist Petrarch ascended Mt. Ventoux, in southern France. That’s may be the first record we have of climbing a mountain when the only motive was the climb itself. That’s the motive Petrarch claims in a famous letter he composed on the evening of the same day to his former confessor, Father Dionigi da Borgo San Sepolcro, an Augustinian monk. Petrarch’s letter makes it clear, however, that he wrote to Dionigi not only to describe the joy of the excursion, but also because he was feeling guilty about the “earthly enjoyment” that the view from the summit had given him. In retrospect he decides that, like St. Augustine (whose Confessions he carried with him to the summit), he should have had his mind on more spiritual questions than his own selfish experience, berating himself for this lapse: “How earnestly we should strive, not to stand on mountain-tops, but to trample beneath us those appetites which spring from earthly impulses.” Petrarch seems to be torn between a Renaissance desire to explore and know the world, and a medieval view that such knowledge is irrelevant, that what he should have understood from the start is that:nothing is wonderful but the soul, which, when great itself, finds nothing great outside itself. Then, in truth, I was satisfied that I had seen enough of the mountain; I turned my inward eye upon myself, and from that time not a syllable fell from my lips until we reached the bottom again.

Well – maybe he was just tired, hungry and cold. But Petrarch’s encounter with the mountain convinces him that what is most worth contemplating is not what he has seen from the summit, but rather what lies within his own soul.

The cover to the author’s new book: Living the Life. Available from Conundrum Press.

But perhaps we protest too much. Maybe the anxiety we feel between wildness and polis is productive, even useful, an achievement, not a problem. Petrarch might not have had his vision of God that day unless he had climbed Ventoux. The complexity of drawing these two things together – our purposeless joy in nature on one hand, our purposeful obligations on the other – shows how much we remain Petrarch’s ambivalent heirs.

Odd how the wilderness and the city, whether of man or of God, give each other meaning. And so I remember: tired, quiet little humanists, friends for life, we rattled down the West Side Highway, rack after rack of glittering lights on our left, the rotting docks on our right, fragments of wilderness in our hair, smelling bad, contemplating sleep and tomorrow’s work, touched by delight and the frigid wind and swirling snow of the Thunderbolt.

Republished with permission. Originally published in Couloir magazine Vol V-2, 1994.

David J. Rothman’s book, Living the Life: Tales from America’s Mountains & Ski Towns, available on Amazon.

Related Posts

Thunderbolt Race 2015

The Thunderbolt Trail website

© 1994

1 comment

Nice story, thanks for the reprint!