If you don’t stick your neck out, don’t leave the ten essentials behind, you’re never going to have an adventure.

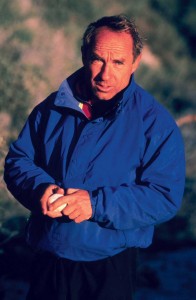

After a six-plus year hiatus, Yvon Chouinard is back in the backcountry — on skis that is. Felled by a broken arm injured during a beach-side bouldering session, Chouinard’s prodigious, storied freeheel career ground to halt through the residual discomfort associated with the injury. While guaranteed a permanent position in the pantheon of America’s ice, rock and mountaineering greats, as well as in the annals of rags to riches business success stories through his founding of Patagonia, the ever-growing number of young, backcountry and telemark initiates may need a refresher on his background and accomplishments.

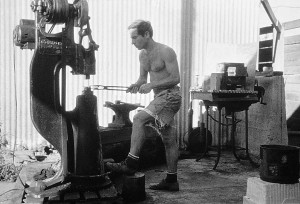

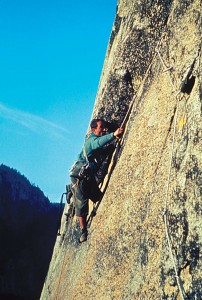

Chouinard helped drive the rapid evolution of climbing over the past 30 years, and had an equal impact on modern adventure skiing; all contemporary mountain skiers owe a debt to Yvon Chouinard. Whether corn skiing in the Sierra, dropping elevator shaft couloirs in the Tetons or powder skiing the San Juans, it’s hard to find a backcountry skier who has gone to battle without gear produced by his offspring, Chouinard Equipment, Patagonia, or the next generation derivative, Black Diamond Equipment. A self-taught blacksmith, Chouinard was born under a sign that left him calibrated to dream, design, re-work, and tinker. While the Patagonia label seems omnipresent, it has been the hardware produced by himself and assembled teams that helped transform backcountry and freeheel ski equipment from over-utilized Nordic and funky, crude ski-mountaineering gear to true mountain skiing implements. Not to mention his graphically lovely, high-spirited, and often philosophically inspirational catalogs that have served as much as a call to arms or mountain manifesto as a vehicle for distributing goods.

Last February (2002), a freeheel skiing trip to Chouinard’s beloved Japan (Hokkaido) provided Couloir with a chance to sit and chat with him about how he got started sliding on snow, gear (of course), and why it’s high time we all got lost.

Brian Litz: Did you get into skiing as many climbers did, as a tool for transportation?Yvon Chouinard: Well, I’m strictly what I would call a mountain skier. The first time I skied was on this volcano in South America—Mount Jima—way down in the south when we went down to climb Fitzroy in 1968.We were making a film. I was with Dick Dorworth, Doug Tompkins, and Lito Tejada-Flores.

BL: This was the famous Fitzroy film and the original fun hog expedition where you drove down to Patagonia in a van, climbing, skiing, and surfing your way southward?

YC: Yes. The other three were excellent skiers and I had never skied before. We climbed these volcanoes and the guys would give me the pack. I’d have to get down the mountain carrying the load while they skied and took pictures. But I basically knew how to glissade real well. Something Fred Becky had taught me—the standing glissade.

I had done a little bit of alpine skiing, but not much. Nor had I lessons or anything. Then I got in with Doug Robinson and those guys on the east side of the Sierra at the same time the guys in Crested Butte were starting to telemark.

BL: The Armadillos?YC: Right, the Armadillos. So I hung out with those guys and started with cross-country skis, trying to turn. And really, we reinvented the telemark turn, but isolated from what was going on in other areas. You know things are invented simultaneously around the world. I really believe that. Every idea has its time. So that’s how I got into telemark skiing — about the time it was all beginning to happen again.

BL: Had you already been designing climbing gear and clothing, and ski gear was just another outlet for your natural design interests?

YC: Yeah, I saw skiing as a way to get back into the mountains to climb and not as an end in itself. We would go into Rock Creek Canyon and do some climbs in the winter and skiing fit right into what we were doing—even in terms of designing gear.

BL: What are thoughts on gear today? I have certainly been hearing you talk about the new Tua Sumos you were skiing on this trip. Has the pendulum swung too far towards alpine in terms of backcountry ski gear?

YC: I am on pretty modern stuff and I am not skiing any better than I was 15 years ago on leather boots (chuckles) and the Toute Neige. The Sumos were fabulous on that junk today, I must say, and I felt really comfortable busting through that crust where my old skis would have submarined. But on the packed slopes I was really wishing I had my old skis. I’m a believer in adapting yourself to the situation rather than going out and buying the absolute best stuff.

BL: Today while skiing, you didn’t carry a pack. You call it “simplifying things.”

BL: Today while skiing, you didn’t carry a pack. You call it “simplifying things.”

YC: Yeah, I drank a bunch of water beforehand and I knew I was not going to get thirsty. And there was no avy danger. I wouldn’t even think about carrying a shovel or anything. People offered drinks, which I’d accept of course (laughs). I take great pride in being able to go lightly. I used to go into the Wind Rivers without a tent and always found a way to get out of the storm. I’d sleep under an alpine fir. You may have pine needles in your face. In winter, dig a snow cave.

BL: Do you feel that today’s skiers and climbers are too focused on numbers? Being competitive about how much vertical they gain, how hard a route is?

YC: It has probably always been that way. You know, ego gets in the way. I can’t stand to follow a guidebook, climbing or skiing or otherwise—or a topo. Or to follow chalkmarks. I think the more you can do on your own, the quicker you progress and evolve. People follow a guidebook because they need to minimize the unknown. It’s important to them and yet it’s such a stupid game.

YC: What’s wrong with getting lost? It may be the best trip of your life. You can’t get lost in this world anyway! In the lower 48, the most remote spot is a little piece of land in the Teton Wilderness—between Jackson and Yellowstone, 23 miles from the nearest road. That is as remote as you can get.

So that means you are within a day’s walk of a road. You can’t get lost. In fact, you should get lost. You know, if you don’t stick your neck out, don’t leave the ten essentials behind, you’re never going to have an adventure. You’ll never have what I consider to be a great day.

BL: Talking about Patagonia, I’ve been struck by how something that began as an outlet for your design creativity has grown into this enormous family around the world. You must take great pride in that.

YC: Yes I do, but it was real serendipity. I never imagined having a business period, let alone what it has grown into. It’s really surprising.

BL: There’s a saying: find something you love to do and do it. This lifestyle becomes Chouinard equipment and the Great Pacific Iron Works, then Patagonia. What is the secret? Having a vision?

YC: For all I say about not getting into all of this equipment anymore, going the other way…still, my head is always reeling with ideas on how to improve things. I’ve given talks all around the country at business schools like Harvard, Yale, and Wharton. All of these budding entrepreneurs ask about the BIG idea that will allow them to have a business.

BL: In many articles, you have been painted as a dour cynic, a curmudgeon and yet I have actually been struck by how happy you seem to be.

YC: Yes, but I am a Buddhist. I’m totally pessimistic about the fate of the world. There is no doubt about it. Every indicator is so negative. I just do what I can about it, so I don’t have the guilt that I am a big part of the problem — maybe just a little part of the problem. Yeah, the good things we do at Patagonia makes you feel good.

YC: Well, I used to go up to Teton Pass just by myself and be the only person up there. Now you can’t even find a place to park. And I think that’s great! Yeah, it’s super crowded but that just means you have to go somewhere else. I am really stoked to see these people in the backcountry.

I tried snowboarding and thought that if I were young again I‘d be a snowboarder because I love that feeling of the Gs—like surfing. And it makes so much sense on all this junk. Like today, those snowboarders were having a ball when we skiers were getting our clocks cleaned.

BL: I have been really impressed by your skiing ability. While powder skiing, your turns were smooth when we were all falling. You haven’t skied in six years and we’ve been hitting it hard, you’re right there, keeping up. Is there anyone who you can point to that helped your skiing, someone that inspired you?

YC: Thanks. Yeah, Paul Parker, Parker really helped me out with my skiing. I said that I never had lessons but I skied a lot with Paul — just trying to keep up. He is inspiring and I have seen him do some pretty amazing things. Once we were crossing the Sierra. I was cutting steps with a spoon just to get my ass down. I eventually threw my pack down this pass and here comes Paul skiing right down. That knocked me out.

BL: What about your advice that your friends should choose your wife and your surfboard for you — does the same go for skis?

YC: Definitely (laughs). Your friends know you way better than you know yourself!

BL: Riding snowmobiles to go into the wilderness to board and ski seems antithetical to me about why we go to the mountains. It seems to be a generational-attitude thing. Like sport climbing, it gets back to an emphasis on instant gratification.

YC: Every generation wants to lay down some marker, some permanent monument to themselves. These bolters see themselves on a mission like a religious fundamentalist on a mission to make the world safe for climbing. They see themselves only in a good light — they are the good guys. I am sure the hybrids see themselves the same way.

This article first appeared in Couloir magazine, Vol. XV-4, Winter 2003.

© 2002

5 pings