Steve McQueen said, “I’d rather wake up in the middle of nowhere than in any city on earth.” Edward Abbey referred to the urban scene as “syphilization.” We read between the lines and suspect a cure for the most subtle of modern maladies, the condition caused by the strained nervous sense of urgency that seems to define life in the city.

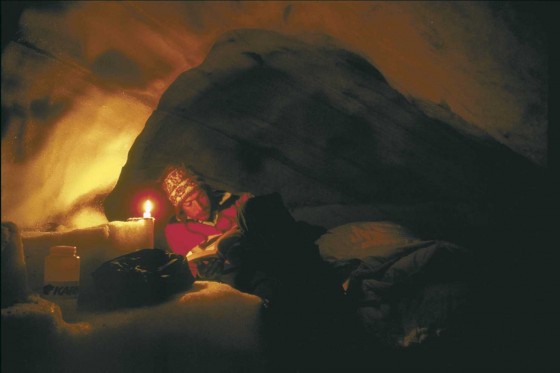

Suddenly my job description is so much more than an expert skier, tireless trail breaker, beast of burden, clever navigator, head chief and avalanche forecaster. In addition, I become confidant, confessor, entertainer, friend and perhaps even the Right Reverend Bardini-First Church of the Open Slopes. It is a job with great responsibility and not just those related to hazard evaluation and risk management.

As a ski guide I have the pleasure of bringing benefit to both. I notice that when people have been touched by the wild lands they are forever changed, forever more aware. They will never again see snow and mountain peaks and wind-sculpted tree trunks, without being effected inside, differently than before they knew of such things, and they will return time and again to get in touch, and be touched. Certainly these are some of the deepest joys of skiing in wild places. It becomes important then, in fact essential, to savor and share these places and feelings. It is interesting that when we travel far afield to ski, what we often find is not just some intoxicating remote landscape but the convoluted topography of our own souls.

This is the value of skiing in, and being with, the lofty terrain of the mountains. These are the advantages of taking the high ground. I have been out into the great hinterlands beyond the backside of beyond, and my life is rich because of it. I am a wealthy man who just happens to be broke most of the time, but I’m in good company.

John Muir stated simply, “Go to the mountains and get their good tidings.”

Bill Koch once said, “The world would be a little better place to live if more folks went cross country skiing.” I must agree with both of my learned colleagues.

Maybe world peace is just a few telemark turns away? Maybe it’s worthy of being a movement? With bumper stickers “Telemarking is Peace – Ski the Backside of Beyond.” Why not? I know of little else like a good day in the backcountry that gives me such incredible tranquility. This is especially true in times when life seems tediously long. But, as we know, life is short. Which reminds me. I saw this rather interesting Sharper Image catalog item. It is a clock of sorts, but this time piece ticks off the time an average person has left to live. Standing and watching it is a little unnerving. A minute goes by and then another and then both are gone forever.

Three-hundred and sixty-five days a year we get the opportunity to have a fresh start at life. A new day and fresh powder reminds those of us that slide on snow that skiing is life. Passion and vitality for living are some of the gifts we receive from skiing, particularly skiing in the great beyond.

One need not travel to the North Pole or the Himalayas or the Andes or any of the high hidden places of the world to know these things. Outback might simply mean skiing out back in the quiet woods behind the barn or perhaps, skiing through Central Park when the first winter grips the city in an icy gridlock. It could be skiing down a New England hillside or across the great expanse of a Heartland corn field. You are out on the backside of beyond when you feel the crisp bite of winter air in your lungs and the sting of wind-driven snow on your face, and when you realize how insignificant you are in the face of such harsh adversity.

That relativity, which comes from knowing the wild places, is essential to our well being and yet we so often stay home, stay inside and insulate ourselves from it. I say, resist the urge to be complacent about experiencing the brutally beautiful joys of the backcountry skiing life. Go my friends. Don’t delay. Lose yourself and maybe you’ll find yourself — on the backside of beyond.

© 1996

Epilog

Alan ‘Bardini’ Bard

1952 – 1997

Died July 5th, 1997 from injuries sustained in a 200 foot fall while leading a climb of the Owen/Spaulding Route on the Grand Teton in Wyoming.

He danced so well on rock (or snow) because he had learned so well how to dance with the world.

—Brian Parks

A twenty year resident of the Eastern Sierra and fifteen year resident of Bishop, Allan was a tremendously popular personality among the mountain sports communities throughout the nation. As an expert professional ski, mountain and river guide, he was truly a guide for all seasons. He was also a prolific professional writer and photographer, master carpenter and avid fly fisherman. His capacity for friendship and “can-do” enthusiasm was inspirational to all who knew him. It will be for his wonderful gift of story-telling, that he will be most fondly remembered. Allan Bard was truly the bard of the High Sierra and will be most lovingly missed.

“Bardini here” was how Allan answered the phone. Soon you would hear tales of great things done and big plans in the making of the future. He achieved many of the goals for which he strove. He set very high standards for himself and others, whether that involved building a house in Bishop or stalking a big brown trout in Patagonia. Indeed, his accomplishments were many and varied, from Alaska to Chili, from Yosemite to Vermont. His feats are legendary, almost larger than life.

The treasure that Allan leaves us is not a check list of adventure but rather the spirit of how he ventured. In the stories he told and wrote, he communicated who he was and how joyfully he lived.

1 pings

[…] best: “He hated to fall.” What Allan wanted to go on doing, according to his recent manifesto “The Backside of Beyond,” was the great work of “bringing people and mountains together to the greater benefit of both,” […]