…Page 2, continued from page 1…

Old school Nordic ski touring – Luddite Dreams

Under firm, morning-snow conditions we top Virginia Pass. The plan had been to drop into Glines Canyon, climb Epidote and Camiaca peaks before camping beside Summit Lake. We quickly nix the idea. The snowpack is thin and the skiing looks terrible.

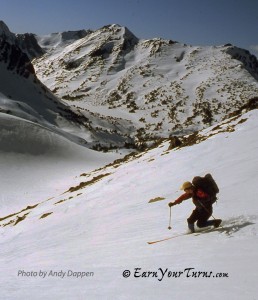

The center of good skiing is obvious from the pass. We must drop to Return Creek, cross a lake basin, then make the long uphill trudge up the expansive bowls capped by Stanton Peak. To the fat-ski, plastic-boot crowd it would be a miserably long haul for the number of steep turns available. But to skiers of our ilk it’s a beautifully rounded tour offering equal parts of flat ground, gentle and steep climbs, and gentle and steep descents. Nils contemplates the distances and asks, “You think anyone else has skied that peak this spring?”Given the state (or rather the weight) of modern ski gear, it’s a reasonable question. We strike off and with the sun hammering the snow discover it’s easy to penetrate the eggshell crust and submarine the skis into the yolk-like snow below. Smooth, delicate turns have Nils barely scratching the eggshell crust. “Heavy plastic boots lack the sensitivity to ski so delicately. Sure, you could ski aggressively and punch each turn, but there’s more elegance in finesse than force.”

We reach a frozen lake, stride across it with the impressive rock walls of Virginia Peak towering above us, than start a long uphill trudge. The corn has softened—ideal conditions for our no-wax skis. The skis grip securely on angles as steep as we care to climb, yet glide downhill nearly as fast as wax bases—all without the tedium and lost time of applying and stripping skins. Again Nils beats the appropriate-technology drum —waxless skis are such good springtime technology, he leaves the skins at home.

I, on the other hand, carry two skinny skins—made by slicing one randonnee skin, longitudinally, in half. Such skins, I argue, are useful for uphill grip in early morning when the snowpack is still icy and for particularly steep climbs. Nils grants me the first argument but rejects the second. “You can climb just as steep without skins and with far less effort.” He mentions the resistance created by skins, “They bleed your legs of energy.”

I’m skeptical.

“Then put a skin on one ski.”I comply. In these corn-snow conditions I discover the ability to climb marginally steeper is not worth the substantially higher co-efficient of friction. I can’t wait to peel the sucker off.

The noon sun hits its zenith and burns through a sky whose blue has bleached nearly to gray. It’s a monochrome world. And a hot one. Were we toting heavy gear, the heat would erode our ambition. But as lightweights, the effort to ski higher is tolerable. We hit the ridge and a breeze freshens the strides leading to the summit.

Before long we’re downward bound dealing with slurpy snows on a steep face. It’s a scenario demanding completely different technique than our earlier descent but my accompanying videographer who created such instructional/informational videos, Beyond The Groomed and Freedom of the Heels is dealing efficiently with the knee-deep glop. Executing quick turns he rises out of the snowpack, changes the direction of the skis, sinks down, and let’s the skis carve momentarily. Then he recaptures the potential energy building in the heavily bowed skis by vaulting upward for another directional shift of the skis. It’s a strenuous but beautiful dance keeping him compact and balanced. The dance also keeps him from generating speeds his gossamer gear cannot control in this snowpack. Rather than nurturing such technique, the modern shortcut to skiing such snows gracefully is employing the sledgehammer of heavy gear.

We stop for a breather and as I pull out the camera to capture this stunning range of white snow, golden rocks and red-barked trees, I toss out questions probing the technique-versus-technology issue. “As a society we try to consume rather than finesse our way out of our problems, ” he tells me. Nils studies the cirque before us, deciding which slopes to ski next, then returning to the topic, illustrates the problem. “I see a lot of people spending $1000 on brand new ski gear who were unwilling to spend a few hundred dollars on the instruction required to have them skiing their old gear better than they currently ski their new gear.”

Nils traverses the cirque and finds a long, 35° slope. He skis the changing snow conditions fluidly by mixing telemark, jump telemark and parallel turns. I ski to the side of his tracks and spend a good portion of the descent battling the glop for balance. A quick look and Nils has not only identified the principle problem but rendered a solution. “Bend your ankles more…you gain an amazing amount of balance with deeply flexed ankles.”

During the next series of turns I bend the knees less and flex the ankles more and can, indeed, feel the improved balance. Suddenly my turns are smoother, my initiation into the next turn faster. It’s a small step in technique, a giant reduction in faceplants.

The margarine-colored light of late afternoon reflects off the snow as we start a two-mile long climb toward a camp at Summit Lake. To the south the white granite cliffs and serrated skyline of Shepherd Crest beckons. We decide to explore its environs tomorrow. Never mind that it looks a long ways off—on light gear if we can see it, we can reach it—if we aren’t distracted getting there.

On the two-mile traverse leading upward to camp, the passing slopes keep seducing us. Without skins to strip and without weariness generated by burdensome gear we frequently drop the packs, crank 20 or 30 turns through perfect corn conditions, then reclimb to our packs and carry on.

We enter the basin containing Summit Lake as the sky turns tangerine and ski to its eastern shores where we camp. From camp we can look across the lake toward the pyramidal peak we skied just hours ago. From this vantage point it appears a long way off. Nils is retracing portions of today’s route with his miniature binoculars and can just make out our descent tracks. “Not exactly McGnarly,” he comments, “But whoever skied way over there must have had an amazing day of Sierra skiing.”

…story continues with a list of lightweight gear here…

This is a rerun of an article first published in Couloir magazine,

Vol. XIV-5, Spring 2002

© 2002

3 pings